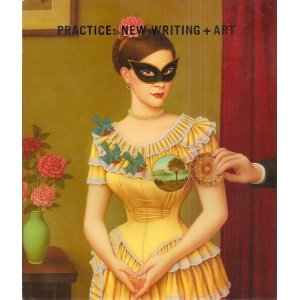

Dan Fost’s literary narrative about a brother and sister’s journey to learn about their father’s World War II experience in the South Pacific island nation of Vanuatu, complete with a trip to the top of an active volcano, appeared in the 2007 edition of Practice: New Writing + Art, a literary journal.

Dan Fost’s literary narrative about a brother and sister’s journey to learn about their father’s World War II experience in the South Pacific island nation of Vanuatu, complete with a trip to the top of an active volcano, appeared in the 2007 edition of Practice: New Writing + Art, a literary journal.

Click here to download a PDF of Dan Fost’s Vanuatu essay from Practice Journal 2007.

The volcano beckons.

My traveling companions say otherwise. The volcano is too active, they say. Tourists were killed there last year. The airline may not even fly into Tanna.

I want fact, not rumor. I don’t know when I’ll ever be in the South Pacific again. I don’t know if this volcano will even exist the next time.

I meet a ruddy-faced American who lives in Australia. He and his wife came to Vanuatu, this unlikely archipelago in the middle of nowhere, to scuba dive. But they went to see the volcano two nights ago.

Over a traditional Vanuatu dinner of yams, taro, lap-lap and poulet fish, the guy tells me about Mount Yasur.

“You must go,” he says. “It’s the most incredible thing I’ve ever seen in my life. Rocks are flying. Lava is spurting up. It’s terrifying — completely terrifying. But I couldn’t tear myself away.”

“It’s so active, they’re talking about restricting access,” he says, leaning closer. “You must go soon.”

My wife, Betty Barker, and I had come to Vanuatu, a small island nation in a remote stretch of the South Pacific, with our friends, Janet and Steve Silva, who planned the trip to trace the military career of their father, George.

George Silva served two years on the islands, back when they were known as the New Hebrides, when James Michener, author of “Tales of the South Pacific,” was cavorting with Bloody Mary during World War II. He spent most of his time on Vanuatu’s largest island, Espiritu Santo, named by a Spanish explorer for the Holy Ghost.

George died young, at age 59 in 1968, after suffering horrific burns in an explosion at home. Janet and Steve were still teen-agers, in classic 60s generational conflict with their parents, and they have struggled over the years to re-discover their father and make peace with his passing. Janet’s own health was precarious, and she wanted to make sure she had this trip with her brother before her own illnesses would consume her.

George’s time in World War II came before Janet and Steve were born. Like a lot of Navy Seabees, George was a little older when he enlisted in the Navy. He had a wife, Lucille, and a job, as a truck driver, in San Francisco, but he also had skills that he thought could help the Allies win the war. He signed up.

He kept a journal, scribbling notes on the backs of checks in a leather checkbook that would otherwise be useless where he was going.

On July 19, 1943, George’s ship, the USS Dashing Wave, crossed the equator. It was hot.

“Now in danger zone,” he wrote.

The next day, he wrote, was a “nice sunny morning, most all on deck laying in sun. We have practice alert signals, all go below deck. All clear and we go back as we were. About one hour passes, we spot a plane, get signal to go below deck.

“It’s the real thing now.

“First shot fired at 12:15 pm. We are zig zagging a lot. Keep firing for about an hour. Everyone on edge and very touchy about the kidding. We are all sweating and waiting. Only thing I have handy to save is my writing material so I put Lu’s picture and my new pen set in my life jacket and stand by ready to go overboard.

“Sure was a relief when all clear came.”

Just what had he volunteered for?

The first thing we notice, as the plane begins its descent, is the runway. It’s not really a runway at all. It’s a big grassy field. Children scatter to make way for the plane.

When we get off the plane, we stand on barrels of jet fuel, and take pictures.

We head into the airport: A one-room wooden shack at the end of the alleged tarmac.

Welcome to Tanna, Vanuatu, South Pacific.

A wild-looking man, with bushy black hair and a bushy black mustache, tells us to get in a car. We grab our bags.

“What’s your name?” I ask.

“Willie Tom,” he says.

Like most people in Vanuatu, Willie Tom wears flip-flops on his feet. He speaks some English.

I stick out my hand and offer the traditional Vanuatu handshake, middle knuckle extended. He reflexively grabs my knuckle between two of his knuckles, pulls back with a loud snap, and asks, in a mixture of surprise and accusation, “Where you learn that?”

Not too many white guys know the Vanuatu handshake, but I had met a barefoot judge on another island who taught it to me.

“On Santo,” I tell him, and he laughs.

Willie Tom drives a white Subaru two-door hatchback. It has little switches for electric windows.

“The windows don’t open,” he says.

It is at least 90 degrees. He has no air conditioning.

It is understandable, though, that the windows won’t open, because Willie lives and drives on Tanna, an island with an active volcano, and when you live on an island with an active volcano, you have to expect to get some ash in the electric window mechanisms.

Willie’s Subaru does have one thing we haven’t seen in any other car on Vanuatu, and that is working seat belts. Because I ride shotgun, with Betty, Steve and Janet in the back, I am particularly grateful for this.

It means that I can safely hold my door open as we drive up and over the long hump of the island. It means that we can breathe.

To help out, Willie also holds his door open. He steers with his other hand.

“If you need to close it,” I say to Willie, “to use two hands, to avoid hitting a cow or a pig or something, go ahead.”

Willie laughs.

The road is, of course, unpaved, and Willie, of course, drives very fast. He points out the sights along the way.

“Football field,” he says. “We play twice a week.”

“Are there many good football players on Tanna?” I ask.

“No,” he says.

He points out a hospital atop a hill.

“How many doctors work there?” I ask.

“Five,” he says.

“Are any of them ni-Vanuatu?” I ask.

“Four,” he says. “Four ni-Vanuatu. One English”

We hit a section of paved road marked with huge craters long past the stage of being what you’d call a pothole.

“Engineers from England built this road,” Willie says proudly. “1980.”

The road, which curves up the long steep spine of Mount Lonionul, enables people to drive across the island, instead of around the coast. For us, that means a one-hour ride in Willie’s cab, instead of three hours. God Save the Queen.

I keep the conversation focused on Willie and Tanna. Janet, Steve and Betty sit quietly in the back, nervous, anxious, suffering from culture shock themselves. My compatriots surely think they should have stayed on Espiritu Santo, where the World War II sites are. On Santo, we had tile floors and running water and breakfasts of homemade croissants, locally grown coffee, and fresh papayas with a squeeze of lime.

We had fun exploring Santo and George Silva’s legacy, and they could have stayed for more. I would have come to Tanna by myself, but they kept the group together, and I’m glad not to be alone in Willie’s cab. The volcano does have some allure for everyone. Steve, a geologist, has a scientific interest, and Janet, a professional photographer, knows she’ll have a good subject. Betty, a native of Oregon, witnessed Mt. St. Helens’ cataclysmic eruption in 1981, and she scaled it years later for a close-up view of the smoldering, regenerating cinder cone.

When Willie’s cab reaches the top of Mount Lonionul, we catch our first glimpse of Mt. Yasur. It is a hazy day, but we can still see puffs of smoke rising from the volcano’s mouth.

Willie drives fast down improbable S-shaped switchbacks. The other islands had neat rows of coconut palms, but we had not yet experienced anything like Tanna’s jungle vegetation.Willie zips through a dense, lush forest — dark vines draped around thick-trunked banyans, black tree ferns, yellow-flowered purau, white woods, and some palms.

Willie dodges cows, pigs, chickens and people. He closes his door in the populated areas, and gives everyone in the thatched-roof villages a friendly toot on his horn.

Amazingly, his horn does work.

When we reach the bottom of the hill, we come to the most breath-taking stretch: the ash plain. The back side of Yasur looms above us like a jagged, rumbling monolith, and at its base it has left a wide stretch of fine, gray volcanic ash. A small lake seems to be full of black ink, but it is only the clear water darkened by the ash beneath it. The only objects marring the sandy smoothness of the ash plain are large boulders heaved from Yasur’s pit — yesterday? today? a century ago? — and tall wooden spikes not immediately recognizable as tree trunks, stripped of greenery by the harsh atmosphere.

I have to close the door of the Subaru for this stretch of road. Ash swirls, sandstorm-like. This is, however, the smoothest road in Vanuatu.

We leave the ash plain and return to a narrow road lined with trees.

“See the leaves?” Willie asks. “Ash.”

They look almost like the survivors of a forest fire, but he is right: They are covered with volcanic ash.

I ask Willie about a special annual ceremony that I’ve read about, known as Nekowiar.

He becomes very serious. He tells me of chiefs from the different islands of Vanuatu, coming to Tanna and painting themselves in ceremonial designs. Over four days, they dance, and chant, and kill and roast pigs.

They never know, he says, until a few weeks beforehand, when the ceremony will be. The tourist office won’t know, but Willie says he will know.

“Give me your address,” he says. “I’ll let you know.”

“We’ll camp out?” I ask. “And cook yams?”

“Yes.”

He pulls the car up at Port Resolution, our home for the evening. It is an assortment of thatched huts perched on a cliff above the ocean, at the end of the earth. The volcano rumbles and thunders.

It is dark by now, and the hosts carry kerosene lanterns as they come to check us in.

I give Willie my business card, which includes more information than he can possibly use — phone, fax, email.

He promises to write, but just in case I need him, he gives me his card. It has a picture of him standing by his cab. The car appears so white and shiny, the photo must have been taken on the day he bought it.

The card gives no address, no telephone number. It says only Willie Tom, taxi driver, Tanna, Vanuatu.

* * * * *

The water at Surunda Bay, on Santo’s northeast coast, was perfect, sparkling clear, glassy smooth. Colorful fish froliced in the turquoise ocean, and sea snakes swam among the underwater plants. Waves lapped the shoreline, and hardened coral tinkled like glass chimes.

No high-rise, no resort, no tourist mob spoiled the serenity of the moment. The beach, the bay, the view looked like they must have looked 50 years ago.

Which was precisely the idea.

Steve Silva stood on the shore of Surunda Bay and thought about that: What it must have been like 50 years ago.

He thought about what peace his father must have derived from going to this same beach, 6,000 miles from his home, and picking up seashells, and cooling his heels in the tropical waters.

What a respite George Silva must have felt from the mobs of men with whom he shared a Quonset hut and mess hall, his fellow Navy Seabees, toiling in tropical heat, fighting tropical insects, contracting tropical diseases while they repaired cars and jeeps and boats and planes, and built roads and runways and more Quonset huts, all in the name of winning the war.

The war was won, of course, and the Seabees were gone, and the islands of Vanuatu were left more or less as the Navy men had found them: jungles and coconut plantations, beaches and bays, island paradises miles from civilization.

George Silva never did get to tell his son all his war stories. But he did leave behind a collection of dazzling seashells. And a photo album. And his journal.

“Sept. 5,” he wrote, in 1943. “Went to Surunda Bay. Picked up some sea shells.”

Like his father on that long-ago adventure, Steve Silva was making his first trip overseas. His sister, Janet, an experienced world traveler, had urged him to make the trip, to clear up questions long unanswered since their father died. Janet, our friend, invited Betty and me along.

Steve had started thinking of the trip last year, when he mentioned his father’s military career to his friend, Katherine, a librarian. Katherine found a naval map of Espiritu Santo, the island where the Allies had their major Pacific base for most of World War II. Steve, a geologist, could relate to maps. He got interested. He wrote to the Navy for his father’s war records.

The records told where George Silva trained, but they didn’t tell where he served. In World War II, the Navy was paranoid about writing down that sort of information. Steve did, however, have his father’s journal, which gave some details about the trip over: the boat, the USS Dashing Wave, left Port Hueneme, CA, at 9:15 p.m. July 11, 1943, bound for the New Hebrides.

George also mentioned his Seabee detachment, the 1007, and that the unit lived and worked in an area known as Lion 1. He also provided other details that, however clipped, painted a real-life picture of things on the ship. “Still quite a few on board pretty sick,” he wrote in the first few days. “Most of cooks sick — walked out. Little rough, kitchen is a mess, trays going one way, men another.”

Steve filled in some of the other blanks by taking a trip to the Civil Engineer Corps-Seabee Museum at the Naval Construction Battalion Center, Port Hueneme, from where George’s ship set sail for the South Pacific. Port Hueneme is near Oxnard, a seven-hour drive from Steve’s Bay Area home. He and Katherine went there and back in one day, returning with a folder full of photocopied records, magazine clippings about the New Hebrides, maps, pictures, and a doctoral dissertation. The photos showed Quonset huts, jeeps and tanks parked for miles beneath the coconut trees — all the harder for the enemy to see from a distance.

A commander’s letter to a family expressed condolence about a Seabee who died of a heart attack, and the date corresponds with that of a funeral George wrote about in his journal. Steve also found an inventory of the dead man’s possessions, down to a pack of Chesterfields and a pack of Lucky Strikes.

“Those kind of details bring it alive for me,” Steve told me in the Los Angeles International Airport, as we waited to board our plane. “I’m sure my father had all the same stuff.”

I could tell in that conversation that Steve had developed a strong mental image of the layout of George’s base. “I want to look out at the view,” Steve said, “and say, ‘That’s the view my father had.’”

About 36 sleep-deprived hours later, counting a rainy layover in Fiji, we landed in Espiritu Santo.

The plane flew over coconut trees laid out in a tidy grid. Swaying gently, their tops laden with young green coconuts, the majestic trees stood more than 50 feet tall. Some had kinks in the middle, a sign of when powerful cyclones bent them nearly in half for an extended period.

Those cyclones also leveled many of the Quonset huts that once housed thousands of men on this island, but were abandoned when the Navy left the New Hebrides at the end of World War II. One of the first plots we visited, according to Steve’s map, had not housed the typical teen-age draftees, but instead was the base for the Seabees. The Seabees were older men, generally, and blue-collar — men with jobs and families, and also with a strong belief in the American mission to win the war. George Silva, age 35, was one of those men.

“Sure good to have fresh water to take a shower even if it is cold and out under a coconut tree,” George wrote on Aug. 9, 1943, expressing relief after salt-water showers on the hot, stinking, one-month voyage. “Lots of coconuts laying around, looks like they are going to waste. Grove belongs to Palm Olive Co.”

More than 50 years later, nearly 30 years after his death, George Silva’s son Steve and daughter Janet stood beneath the same coconut trees. They’ve traveled 6,000 miles to get here, to these improbable islands in a remote stretch of the stunning South Pacific Ocean, 500 miles west of Fiji and 1,200 miles north of Australia.

They looked more like tourists than the children of a World War II vet. Janet wore long sleeves, a big floppy hat, and Teva sandals — a bad choice of footwear, it turned out, to wear in something that is now a cow pasture. Steve wore a Hawaiian shirt, khakis, and a straw hat. He held his map, spread open, about three feet wide.

The map was in black, printed off a blueprint in the Seabee archives in Oxnard. Once top secret, the map showed the layout of the old military base that had become this pasture, this coconut grove. Small white rectangles indicated Quonset huts. Small white dots, in neat rows, indicated coconut trees.

This was the place.

“It’s a nice area to be camped in,” Steve said, sizing it up.

He seemed almost overwhelmed.

“This is really something,” he said. “All those pictures we’ve seen for years and years and years, and now we’re here.”

Our guide, Glen Russell, a ni-Vanuatu with a feel for the history, found the place thanks to Steve’s maps.

He knew the place well: Oddly enough, he had lived there as a child, in an old Quonset hut, while his parents worked on the cattle plantation. Glen is broad-shouldered but soft-spoken, and while his English was perfectly understandable, he sometimes phrased things in a funny way.

“Maybe your father’s been touching all this,” he said.

“That’s what I was just thinking,” Steve said.

He walked through the coconut grove. “I’m glad they’re here,” Steve said. “The same trees. I have pictures of these very trees.”

* * * * *

The voice at the door is soft and sweet, a gentle wakeup considering that it is 4 a.m.

“Excuse me,” she says. “You ready to go see volcano?”

In five minutes, Betty and I are dressed and out of our little grass bungalow. With a flashlight, we find our way through the densely foliated paths to the pickup. Janet and Steve follow shortly.

Vanuatu has many volcanoes on its 80 islands, but none so active as on Tanna. There, Mount Yasur is billed as “the world’s most accessible volcano” — a bit of a joke, really, when you consider how inaccessible Vanuatu is in the first place. On the other hand, it’s hard to argue with a claim of accessibility at a volcano where you can walk right to the very rim and watch orange-hot rocks spew from a lava lake below. Three tourists died last year when those rocks struck them. That’s accessible.

A volcanologist would term Yasur a cinder cone — one with the triangular peak of a classic mountain, formed mostly by the accumulation of loose cinders and ash. Yasur is a relatively small volcano, but is genetically related to its more notorious cousins within the Pacific’s “Ring of Fire,” where so-called stratovolcanoes like Mt. St. Helens and Mt. Pinotubo make world headlines with spectacular and deadly eruptions.

Kathy, of the soft sweet wakeup voice, is our guide. She is 19 and striking. She keeps her hair short, like many American women. She wears a fashionable windbreaker that Land’s End might describe as cobalt blue and canary yellow, and while most ni-Vanuatu people wear the simplest flip-flops, Kathy sports very modern footwear that’s a cross between tennis shoes and Teva sandals. She grins almost all the time. She speaks English well, and also knows French, and it’s obvious she speaks Bislama, the pidgin English that has evolved into the national language of Vanuatu. (Although the ni-Vanuatu speak it with utmost seriousness, Bislama strikes some comic chords with native English speakers: For instance, a billboard for a cracker company reads, “Lee’s Makem Goodfella Biskit.”) She probably speaks a tribal language as well. Vanuatu, a nation of only 150,000 people, is one of the most linguistically diverse countries on earth, with more than 100 different languages — not dialects, but languages. On Santo, we even met a Stanford University linguist studying three of those languages, who marveled at their distinctions.

Kathy has never left Vanuatu, not even on vacation, not even to Fiji, or New Caledonia, or the Solomon Islands, all less than 500 miles away.

Clearly there is good money to be made working the volcano: Willie’s cab ride costs 200 Vatu, or $20 U.S., per person. The round-trip ride up to the volcano is another 200 Vatu each. Passes to actually see the volcano are yet another 200 Vatu, and lodging at Kathy’s huts at Port Resolution still another 200 Vatu. For the four of us, that’s a total of $320. Still, I wonder: How many American 19-year-olds can speak four languages well and, of those who can, how many would make a living by traveling, every day, to the potentially deadly rim of an active volcano?

The best way to see the volcano is at night, when the burning rocks light up against the night sky. The night before, our guides deemed the weather too wet to go up — on a drizzly night, steam would obscure the view into the volcano’s crater. But we only have one night; hence the 4:00 wakeup.

Hoping for clearer weather, we pile into the pickup. Steve and I chivalrously sat in back with Kathy. Janet, stomach ailing from an apparently disagreeable meal, sat up front with Betty and Samuel, the driver.

One advantage to the darkness, incidentally, is I don’t notice until many hours later that Samuel’s tires are completely, absurdly bald.

We rocket into the forest night. I cling to the side of the truck for dear life. Peering into the cab, I see the speedometer hit 60 miles per hour. Through his cracked windshield, I see the unpaved road twisting ahead. Two rutted tracks in the dirt lead the way. Samuel’s pickup clings to the tracks like a roller-coaster, up and down hills, around blind curves, past darkened villages. An owl flees our path at one point, a pig at another.

The view out front is terrifying. To the side, trees whiz past like fenceposts, like pages in a flip-book movie. Only looking back provides any comfort, as the receding view is a lot easier on the stomach — except, that is, when a coconut drops from a 50-foot tree-top, missing the bed of the pickup by a yard or two at most. If our timing is off by two seconds, I’m a dead man. I look, wide-eyed, at Kathy. She’s laughing.

Samuel hits the ash plain, the only part where we’re not on a formal road. It’s a smooth, windswept open area covered with gray volcanic ash. He zooms across this too, but then suddenly, at a rock wall, he slams on the brakes. Kathy laughs again. We’re lost.

The disorientation is only momentary. Kathy straightens Samuel out, and he stops at a small village of thatched huts. He gets a key to a gate to the road leading up to the volcano, waking someone up to do it.

We’re not there yet, but I hop out of the pickup. I stretch my legs, happy to touch the earth again, regardless of the violent rumblings beneath it.

I am surviving the ride. Surely I will survive the volcano.

* * * * *

I’ve never had to do what Steve is doing. My father is still alive. I think about the baseball games I’ve gone to see with him, the plays and museums and restaurants he’s taken me to, the summer I spent working in his law office, all the family gatherings. I think about how my own life has been free, literally and figuratively, of the sort of explosion that claimed George, and that broke his wife’s heart.

George Silva died too young, and his wife, Lucille, only survived him by two years. Worse, they died at a time when the generation gap was driving a wedge between them and their children, and they never quite made peace.

George was brought up on conservative farm values. He believed in corporal punishment, respect for elders, hard work. Janet and Steve were teen-agers in San Francisco in the 1960s. In the Silvas’ case, it probably didn’t help that George and Lucille were 10 years older than other parents of the era.

“We were a disappointment, to say the least,” Janet said over dinner in a Berkeley restaurant, after the trip. “They were more fearful about what we were doing wrong than pressuring us to be doctors or lawyers.”

Janet was at San Francisco State, and hanging out near the Haight-Ashbury. Steve flunked out of City College, which he says “was almost impossible to do.” A stint in basic training, however, made him realize he needed to get his act together.

A friend helped him get into the Reserves, thereby avoiding the draft and Vietnam. “Except for being a kid watching World War II movies, I never had any desire to be a soldier,” he said. He returned to school, got his grades up, and got into UC Berkeley. He showed an aptitude for science and eventually landed a job with the U.S. Geological Survey.

Janet, too, went on to graduate, and carve an equally successful, if less conventional, series of careers as a businesswoman, artist and photographer.

The failure to reconcile completely with their parents nagged at them. They thought their parents would be disappointed at the absence of grandchildren. They wished their parents could have seen the successes in their lives. They wished they could have gotten to know their parents as adults themselves.

“I think I would have had a decent relationship with them as people,” Janet said.

“I had a good relationship with dad,” Steve said. He recalled going to the San Francisco Golf Course on Monday nights, caddies’ day. “We’d go through a break in the brush,” Steve says. “He knew the groundskeeper.”

Even though George Silva never traveled farther than Oregon or Nevada, Steve and Janet thought he might have joined them on the journey to Vanuatu.

“I wish he were around and in his 60s or 70s,” Steve said. “We could have gone with him. To be over there with Dad would have been fun.”

* * * * *

Vanuatu provided an ideal locale for pondering the world’s religions.

For centuries, the ni-Vanuatu practiced a spirituality guided by their closeness to the earth and its bounty. They recognized their reliance on the web of life, and paid tribute with rituals and dances.

Vanuatu’s traditional tenets made even more sense when one sees the results of imposing Christianity on such a society. Every island has villages of Catholics, Baptists, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Assemblies of God, you name it. In a trip to a local village, we saw how people used to live spread along the river, but the missionaries congregated them, Western-style, into a tight community. One result was that now the water was fouled from having so many people packed into such a tight space.

Whenever we told the ni-Vanuatu that we were from the U.S., they assumed we were either Peace Corps workers or missionaries, and we bumped into a few missionaries on our trip.

On Tanna, not far from the volcano, there’s even a cargo cult, known as a Jon Frum village. It’s so named because the people believe that “Jon from America” will one day bring boatloads of cargo. The village took as its symbol a large red cross. We saw it from Willie Tom’s taxi as he sped past the village.

The notion of a cargo cult follows a weird sort of logic, if you think about it. Consider what happened in the 1940s: People living a Stone Age lifestyle suddenly saw massive ships full of modern supplies dock at their shores, and unload thousands of men toting crates of food in bottles and cans, and driving jeeps, and flying in airplanes. There could be no rational explanation for it.

The story goes that someone told the villagers, at the end of the war, that all of those good supplies would return some day if they maintained their old ways. In one fashion, this preserved the lifestyle, in that the villagers still live in thatch huts with dirt floors, cooking yams. But as an Australian anthropology professor told me on my flight to Vanuatu, it’s not really the old ways: “There were never cargo cults back then.”

* * * * *

One old custom that survives is the land-diving of Pentecost Island. Each year, young men erect six to eight-story wooden towers, tie long vines to their ankles, and leap to the earth below. If the liana on their foot keeps them from hitting the ground, the belief goes, the community is assured an excellent yam harvest that year. The exercise predates European arrival in the late 18th century, but has become something of a tourist attraction in modern times.

While on Santo, I met a man from Pentecost, John, and I asked him whether he was a land diver.

No, he said. The ceremony was just last month, he said, and one man landed badly.

“I heard about that,” another man said. “How’s that guy doing?”

“Not good,” John said. “Paralyzed from the neck down.”

And to think: Some lucky tourists got to see it happen.

* * * * *

We are not strangers to earth’s violent forces. The four of us survived the big earthquake that shook San Francisco in 1989.

George Silva, too, had to have been aware of nature’s destruction, even if he wasn’t born until two years after the earthquake and fire that devastated San Francisco in 1906. The quake must have been felt even slightly in Arcata, 300 miles north, where his parents ran a dairy ranch. It certainly remained a topic there for years afterward. Its shadow still loomed over San Francisco even 20 years later, when young George moved south to try life in the big city.

George was one of 13 children, a typically large farm family of the era. Kids on the ranch had to work, from an early age. “All those boys were handy,” Steve’s Aunt Emily told him.

Unlike most of his brothers and sisters, who stayed on the ranch, George couldn’t wait to leave. The farm boy moved to the Barbary Coast, the bright lights of San Francisco.

In a way, he was keeping a family tradition. His parents had left their own chain of islands, the Azores, a Portuguese colony off Africa in the North Atlantic Ocean, coming to California to establish the dairy. And their predecessors had left Portugal to colonize the Azores.

The Catholic farm boy married Lucille Kaplan, a Jewish girl drawn to San Francisco from a different sort of small town, Portland, Oregon. Years later, after both George and Lucille had died, Janet and Steve learned for the first time that each parent had been married once before. Each marriage ended in divorce, and with no children, and so, the thinking apparently went, why confuse our kids with this bit of unnecessary history? The discovery was not without irony, however, as Janet and Steve reached midlife having never married or had children. They appeared quite comfortable in a life in which a rich network of friends served as a surrogate family.

Before Janet and Steve were born, the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor and the nation went to war. The West Coast felt particularly vulnerable. George Silva, married for only six months at the time, signed up for the effort.

He was a blue-collar man, skilled at many tasks. Janet had a bracelet he made for her mother, fashioned from airplane sheet metal on Santo. In his long career as a San Francisco street sweeper, he often put his motor broom on idle and leapt off to pick up some treasure he saw on the curbside. Steve and Janet reminisced about George one morning over French coffee and croissants at KC’s Cafe on Santo.

“When I would ride with him in his motor broom, he would sweep at an exclusive golf club, and we would go in on caddies’ day,” Steve said. “He knew people all over the city.”

“The motor broom had two complete sets of controls,” he recalled. “He’d drive curb side. I’d sit at the other wheel. It was fun. In residential neighborhoods, he’d pick up little kids.”

Steve remembered the garage being full of stuff.

“He collected screws,” Janet added. “All organized. We never had to go to the hardware store. That was our father. He could make anything out of anything.”

Once, Steve told his dad he needed a new wallet, and George emerged from the basement minutes later with a box of wallets gleaned from gutters. George’s accumulative habits begat Janet’s own cluttered basement, with pieces of old tools and a corner full of broomless broomsticks. “I’ve got some of the half-burnt candles and the string and tape collections,” she said, and Steve countered, “I’m worse than Janet.”

George drove the motor broom for 18 years after the war, finally getting promoted to general foreman. “I think he enjoyed the motor broom more,” Steve said. “As general foreman, he had to wear a suit. There was a lot of pressure. He had a boss.”

Those qualities made George a perfect Seabee, at least according to a couple of vets we met while poking around the World War II ruins on Espiritu Santo. “It wasn’t Annapolis tradition that won the war,” Bill Hanley told Steve over dinner on a warm night at the Bougainville Hotel. “It was every reservist. It was your father. He volunteered.

“They said somebody needs your skills in the South Pacific or Africa or wherever, and they would go. And they were good. They could repair anything. They were remarkable guys.”

Hanley, now 75, and his pal Bill Glennon, 78, were on their own historical mission in Vanuatu. They came to find the signal tower where they spent their tour of duty.

They found it that morning, they told us, and now they’re done. “We’re satisfied,” Bill Glennon said. “We saw the view.”

“We were up there looking at that view all of our duty hours,” Hanley says. “Except with hundreds of ships — cruisers, battleships, destroyers.”

They pulled out a photograph of two strapping young sailors, shirtless, stomachs flat as Nebraska. A closer look and the faces came into focus — the same sunny smile on Bill Hanley’s face, now fleshed out and decked with white hair, and the same leonine confidence that showed through Bill Glennon’s now mature jowls.

“Neither of us remembers it being uncomfortable,” Bill Glennon said. “We were both here over two years. We were children, really.”

“We were 21 going on 14,” Bill Hanley said.

“We both remember the weather,” Bill Glennon said. “It would be totally clear, and then it would pour, and a half hour later you would be dry.”

“I remember the musty smell of the place,” Bill Hanley said. “The copra. The jungle. The dampness.”

As they told us their stories, the war came alive. We had read Michener before the trip, and learned of daredevil pilots, of endless boredom on atolls sticky with heat, and of men perishing in grisly combat. But that was fictionalized. Hanley and Glennon recalled specific incidents. “I was in that tower on the tops of the coconut trees,” Bill Hanley said, “and a New Zealand pilot tipped on his wing and flew in right between a row of palm trees. He was waving and smiling, clipping the palm fronds. They were 19 and 20 years old and they were absolutely fearless.”

From their tower, they saw it all — the endless stretches of nothing, and the vital bursts of action.

“While there were between 100 and 200 ships in the channel, most of them were dealing with pretty mundane things,” Bill Glennon said. “Bringing in supplies. Taking out supplies. What really counted were the war ships going up ‘the slot,’ taking on the Japanese, coming back and dropping off wounded.”

Bill Hanley remembered listening on the radio to an air battle over Attu, in the Aleutian islands. The Americans had sent fighters from San Francisco to fend off a Japanese move to Midway Island, or even to Alaska. “My recollection is we lost 15 planes,” Hanley said. “After a while, the fog started rolling in. There was a pilot in the water, talking to us, telling us where he was.”

There the signal callers radioed for help, but none arrived. Hanley kept talking to the wounded pilot, alone in his plane, freezing, terrified, dying.

“In the end, he was crying,” Hanley said. “‘Don’t leave me. Don’t leave me.'”

Michener’s Pulitzer Prize-winning book, “Tales of the South Pacific,” did plenty to romanticize the war. He spun exotic adventure stories, later set to music by Rodgers and Hammerstein in the most popular Broadway spectacle of its day. In Michener’s war, the evenings were enchanted. Young nurses plunged headlong into love with mysterious French plantation owners. Tropical air and fragrant plants lured upright officers into passionate flings with island girls. The Navy’s “big dealers,” bare-chested and tattooed, roar through a landscape of turquoise and alabaster.

Yet Michener recognized the brutality of war. He saw it, and he wrote about it. His book ended on a somber note. After a bloody battle with the Japanese — a fight the Marines naturally win, but in which many of the book’s most beloved characters perish — the narrator walks through a military cemetery.

“I was appalled by the relentless manner in which one dead plus one dead plus one dead add up to three white crosses,” Michener writes. “If you sit at home and read that two hundred and eighty-one men die in taking an island, the number is only a symbol for the mind to classify. But when you stand at the white crosses, the two hundred and eighty-one dead become men: the sons, the husbands, and the lovers.”

The narrator walks through the cemetery.

“I wondered where the men would come from to take Commander Hoag’s place,” he writes. “Throughout the Pacific, in Russia, in Africa, and soon on fronts not yet named, good men were dying. Who would take their place? Who would marry the girls they would have married? Or build the buildings they would have built? Were there men at home ready to do Hoag’s job? And Cable’s? And Tony Fry’s? Or did war itself help create replacements out of its bitterness?”

“I’m probably one of the last guys who wants to hear their stories,” Steve Silva muses after meeting the old vets Hanley and Glennon.

Steve came of age in the Vietnam era. Even though the movement drew much of its fire from his hometown of San Francisco, Steve was not fiercely political enough to protest. By the same token, even though his father never saw the war from the front lines, always working in the relative safety of the repair bays in Santo’s Quonset huts, he retained enough memories of his wartime experience that he hoped to spare Steve a trip to battle.

When Steve was 17, and due to receive a draft card, George took him to various reserve units in the Bay Area, trying to find him a state-side assignment.

The father never got to complete the task for his son.

One night, in the spring of 1968, while Steve and his mother watched “The Smothers Brothers” on television, George worked in the basement, as he did nearly every night. He used gasoline to wash parts of the engine on his jeep, which wasn’t uncommon, Steve says: “It’s a powerful solvent.”

Steve thinks his dad must have tipped the can over, and the liquid ran to the natural gas furnace. The vapors must have hit the pilot light.

Then came the noise Steve would never forget.

“Simultaneously, there was the sound of breaking glass, and rushing wind — kind of a rumble,” he says. “It was the gas exploding. It was not like dynamite. It was a big ‘Whoosh.'”

George called for Steve. Steve ran downstairs.

“Flames were everywhere,” he says. “I went into the furnace room. Flames singed my eyebrows, my eyelashes, my hair.”

George ran the other way. “He went upstairs and rolled in a rug and got the fire out. He was lying on the front lawn, moaning. You could see his clothes were just ash.”

He had third degree burns on 80 percent of his body.

“They didn’t expect him to live through the night,” Steve says.

The house was half destroyed by fire, as cans of paint, George’s hunting guns, and all the other stuff accumulated over the years burst into flames. The stench would never leave, not even after the Silvas moved away. “For years,” Janet says, “you had things that smelled of the smoke.”

George lived for another month. Doctors tried skin grafts, but he had lost his nose and ears. He wouldn’t have been able to use his hands again. “It’s not how he would have wanted to live,” Steve says.

For two weeks, George was able to communicate, sometimes complaining, and sometimes offering parting advice. “One of the last things Dad said to me was, ‘Keep on swinging,'” Steve says. “He thought I could make a living playing golf.”

Without his skin, George had no protection against infection. He died of pneumonia.

In his early weeks on Santo, George’s diary entered into an unusual rhythm.On some days, he collected sea shells. On others, bombs dropped in his area.

These he must have viewed as the only newsworthy events, and even those lost their value as occasions worth recording. On Oct. 3, he noted, “There is a big ship convoy laying out here now about 465 ships. Ready to move north; looks like a big push soon. Lots of wounded men being brought in from the north and a lot of men being shipped up to replace them. The hospital ship is here now. Can see it from my hut. P.Call Charlie hasn’t been here for two weeks now. The longest stretch we have had without any bombs being dropped.”

He then stopped scribbling on the backs of the otherwise worthless checks. Maybe it was stashed in a duffel bag, only to be rediscovered as the war wound down. But he wasn’t finished writing. As if in a movie — as if all the jeeps and boats and planes that he repaired don’t merit a mention, as if all the antics memorialized so faithfully in Michener barely registered a blip on his consciousness — the next entry is headed, “Two years later.”

George was heading home.

Steve later told me that he read George’s diary while he sat on the receiving dock in Vanuatu. “He writes that ‘we just got the news to lash our gear in a sea-going fashion,'” Steve said. “I could feel that. I was anxious to go for that reason. I could imagine being there for two years — it’s a long time, just aching to get on that boat.”

Did George know what was going on in the world? On Aug. 6, the day the U.S. dropped the atom bomb on Hiroshima, George wrote, “Laid around all day — good chow.”

He boarded his ship, the President Monroe, on Aug. 8. “It’s a troop transport but not as good as the tub we come over in,” he wrote. “Quarters close and hot as hell. Capacity 1,500 peace time, 2,200 this trip.”

On Aug. 9, when the bomb was dropped on Nagasaki, George wrote, “9 a.m. Just had chow, been in line since 6:00 am. I think I’ll miss lots of meals this trip. Wears you out waiting to eat. Had a good sleep. We are still docked, taking on supplies. Parked right in front of our old 1007 area. Came aboard exactly 2 years to the day that we landed here. 2 pm. Just pulled away from pier. Heading for canal.”

One day he did get some news.

On Aug. 14, 1945, George wrote:”12 noon — Just announced over speaker war is over. Everyone sure happy. Ships cap said a prayer as no chaplain aboard. The days are sure long and the ship is really crowded but we are glad we are on our way home at this particular time.”

Japan surrendered and America broke out into spontaneous celebration. All work stopped and Champagne flowed and strangers kissed in Times Square. Yet to these men who fought and won the war, the subject of paramount interest was the shifting weather and the shrinking distance between the President Monroe and the Port of San Francisco.

That equatorial heat was cooling off. For George, a guy who lived his whole life on the foggy coast of California, a bone-chilling salt-spray cold must have felt pretty good.

August 17, he started counting down the miles: 2,845 to go. August 18, 2,445 miles. August 20, pass Pearl Harbor. August 21, 1,394 miles to go. August 23, 631 miles left.

On August 24, 1945, George Silva made his last entry into his journal.

“8:00 am,” he wrote, “361 miles from Golden Gate, weather cold.”

Nice and cold.

* * * * *

Samuel drives on, through the timberline, onto the part of the mountain where vegetation cannot survive. Are we close? The pickup struggles up another few hundred yards, and stops.

Kathy grabs a big flashlight and takes off up the path. There’s a wooden fence, but the farther we go, the less fence there is.

It’s not yet dawn. The ground is wet and bleak. A wind blows from the path toward the volcano, taking with it the sulphur smell that would surely be wafting over us. But the ash doesn’t blow away. Our clothes, our hair, our pores get covered, permeated, with a fine layer of ash.

Steve, who always walks briskly, is right with Kathy. I try to keep them in sight, but I lag, keeping an eye on Betty and Janet as well. Janet’s not feeling 100 percent, and she moves slowly. Samuel is waiting at the truck. At least, we hope he’s waiting.

The wind howls and, from somewhere beyond the horizon, the volcano rumbles. Loudly. Gases at the center of the earth are mixing with magma, creating a stone soup that can reach 2,000 degrees at the surface, and can hurl deadly lava bombs thousands of feet through the air.

Betty and Janet don’t have adequate lighting and they don’t have a lot of confidence in the trail. I run ahead and grab Kathy, and tell her to escort Betty and Janet. My adrenalin pumps so hard, though, that I can’t bear to backtrack.

In a few moments, we’re all together at the top. We had been told that the rim was closed, that the view would be from a lower point, but this sure looks like rim to us. Steve stands at the edge of a cliff that drops untold hundreds — thousands? — of feet. I’m certainly not going to peer over to gauge the distance. The site is not exactly maintained with U.S. National Park Service standards; never mind an interpretive sign, this viewpoint doesn’t even have a fence or a guard rail.

It’s still drizzling, and steam fills the crater. Wads of lava shoot up to the level of the rim, or higher, and then float back to the pit, as if in slow motion. A big cloud of ash and smoke and steam hovers above us. Occasionally, the wind blows the cloud aside, giving us a view of the lava lake far beneath, glowing neon orange in the black void of the volcano. In the clearing, Steve wrote later in his journal, he can see that “the floor is mostly solid with glowing fissures and hot spots that spit up a relatively small continuous shower of hot rock.”

Such clearings are only temporary, as the volcano lets loose a tremendous roar, sending skyward another huge plume of ash. The sound is like that of a jumbo jet taking off right below us, echoing through canyons, bouncing off the barren crater walls.

“I’ve seen enough,” Betty says, shouting to be heard. Janet looks visibly ill. She hasn’t even taken out her camera for fear that ash will forever damage its finely tuned inner workings. They leave. I go to where Steve and Kathy stand, right at the edge.

Steve is fascinated, transfixed. What is he thinking? Is he a geologist, absorbed by the front-row display of earth’s fiery forces? Or is he a son, mourning his immolated father?

Steve, fortunately, doesn’t tell me whether he’s scared. In his journal, he wrote, “It’s so windy, I don’t stand as close as I might, afraid that I’ll be blown two steps forward and into the caldera.”

Kathy’s windbreaker is flapping. Could the wind carry us right over the edge? Kathy continually apologizes for the weather. “Usually it’s not like this,” she says, gesturing at the pyrotechnics below. “Usually you see more.”

Do I feel cheated? A little, but I’m also fearful enough to know that any more spectacular a display could provide more terror than I really need. Steve says later, “You know that ledge we were standing on? We have no idea what was beneath it. It was probably just a thin shelf sticking out over the crater. It probably crumbles and falls in every now and then. That’s probably why there’s no fence there.”

I check my watch. It’s been 10 minutes, and I promised Betty I wouldn’t linger. I grab a grapefruit sized chunk of black lava, jagged and sharp, and stuff it in my jacket pocket. I try a few photos of the crater but they only come out as a few streaks of orange against a black background. On the ride back, we’re pretty quiet, but I do ask Kathy a question. “What will happen,” I ask, “when someday, Mount Yasur erupts, really blows, like Pinotubo, or Mount St. Helens?”

“Ha ha,” she says with her girlish giggle. “No more Tanna!”

* * * * *

For Steve, the drama of Vanuatu did not come at the volcano.

It didn’t even come, it turns out, at the places where I thought he felt it most, where I detected the most visible reaction: on the shoreline at Surunda Bay, or poking around the barracks area where George’s unit the 1007 lived, or talking to the two old vets.

It came much earlier, on only our second full day in Vanuatu, when our guide Glen took us around Santo to the old military sites and we saw the first building that was recognizable from one of George’s photographs: the French Catholic church, Saint Michel.

It was a plain wooden church on a small hill overlooking a bay, with a big breadfruit tree in front and low-slung school buildings and dormitories surrounding it. From George’s photos, we could tell that extra rooms had been added since the war. I took a picture of Janet and Steve in front, posed exactly as George had posed his friends 50 years ago, and then we went inside.

Steve recorded his thoughts in his journal.

“I imagine dad sitting along center row, five or six pews back,” he wrote. “Very emotional. Dad probably just went now and then, but just to know that he was here as a young man and saw what I see now was an indescribable experience.

“Things are beginning to change. Images are solidifying. It feels good to me for the real image to replace the imaginary one. It’s like solving a mystery, or finding something you thought was lost for sure. It’s not so magical now, but better. It’s real, a place Dad lived and worked for a while. The climate is real and tangible and the views, and roads, and the water. The transition is a funny thing. I’m walking down an ordinary road in the 1007 area and trying hard to go to the image that contains dad, but then he comes to me. It was an ordinary road when he was here.

“It’s a different time now. The 1007 area is being used for another purpose. I would like to have seen everything preserved as it was then but possibly it’s better to release the space that those things occupy to create new events and a new history. People are living all over the 1007 work area and some have built right over the cement slabs. I think that probably no one there knows what those slabs were used for. They know that they were poured by the American Navy during WWII and that they’re still serviceable to build on.

“It’s sad to me to think that I may be the last person to be interested in the 1007. After I leave the island and the last few vets are gone, no one here will know, or probably care, what went on here during the war. I may be the last person to say goodbye to the 1007.”

* * * * *

Epilogue

When Janet Silva made the trip to Vanuatu, she had already been living with the autoimmune disorder lupus for a few years. She didn’t talk much about the illness, and never once complained about it on the trip. But a few months after the trip, she was hospitalized and put on a respirator. At first doctors thought she might have contracted some tropical virus, but as time passed they realized that it was symptoms of the lupus.

Janet was able to celebrate her 50th birthday in good health, but once again the disease knocked her back into the hospital. Doctors determined that she was not capable of eating — that her body could not tell her windpipe from her trachea, and her subsequent aspiration of food into her lungs was causing life-threatening pneumonia. A tube was inserted into her stomach, and she took all her meals from cans hooked directly to this tube.

Still, she refused to slow down, and spent four months of one winter at a friend’s place in Australia. She tasted food on occasion; she found that few social occasions or gatherings could be conducted without food. She ultimately decided that life without eating was not worth living, and she began to dine on her favorite foods — organic salads, tropical fruits, juicy hamburgers.

In May, nearly two years since the Vanuatu trip, she fell ill again. When Janet returned to the hospital, Steve set up house at her apartment, and sat for hours in or outside her room. Dozens of friends came by, but could only look, or talk, or touch. Janet might squirm uncomfortably, but seemed otherwise unaware of the outside world. Around midnight on June 10, she died.

As her only immediate survivor, Steve was left with all the unpleasant tasks: Sorting through her paperwork and possessions, arranging a service, handling her cremation. This last job he undertook with characteristic diligence. In the company of two friends, he went to the Neptune Society crematorium, and began quizzing the workers. How are the ovens made? What happens to the body? His questions revealed the curiosity that serves him so well in his work in the U.S. Geological Survey labs, as well as the sincere interest in the ultimate fate of his sister.

The workers explained that the ashes that emerge from their kilns are only a small physical remainder of the body. Most of the departed is converted into chemical gases, which waft through the chimney and return to the atmosphere.

As Steve walked outside the building that warm summer’s day, he looked up, and felt that Janet was where she should be. All around.

I too am going to Santo to hopefully find the places you are talking about. My father, Joe Ward was a member of the 1007. Your essay is helpful to me and I value the information. If you have any sources of information that I might use, I would appreciate it.

Randy:

You will have a great trip. It’s been nearly 15 years since I went to Santo, so I will be interested to hear your impressions and whether anything has changed. I definitely recommend Glen Russell, who I think works with Butterfly Tours – he can take you to some beautiful spots.

I see that the Bougainville Hotel I wrote about is now Coral Quays Resort. I remember meeting the WWII vets there. My sense is that’s a good place to connect with folks on trips that are similar to yours.

Best of luck and please let me know how it goes.

Dan

PS you can reach me at danfost (at) gmail (dot) com