A decade after Moneyball, the cult of Billy Beane is alive and well—perhaps nowhere more than in Silicon Valley.

By Dan Fost

Sept. 26, 2014

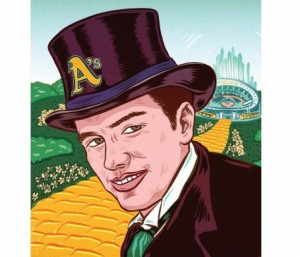

Billy Beane is so over Moneyball. “I’m sort of sick of me,” the Oakland A’s general manager tells me over the phone in early August. You can’t entirely blame him: In the 11 years since Berkeley author Michael Lewis’s bestselling book—and the subsequent Brad Pitt–starring film—made Beane arguably the most famous baseball executive since George Steinbrenner, he’s gone from behind-the-scenes wonk to household name to unwitting (and sometimes unwilling) leader of his own cult of personality.

Especially now. Earlier this summer, after one of the best early A’s seasons in a quarter century, Beane pulled off a series of audacious all-in trades, jettisoning popular slugger Yoenis Céspedes and a few high-ranking prospects in order to acquire aces Jon Lester and Jeff Samardzija and assemble the deepest pitching rotation in baseball. The moves were both appreciably gutsy and potentially ruinous, and as of press time, Beane’s bullishness had yet to be entirely validated: The A’s hit their first rough patch of the season shortly after the trades, going 14–20 (and dropping out of first place) in the five weeks that followed.

But the thing about being a symbol is that sometimes the specifics matter less than the narrative. (Consider, for example, the book that made Beane famous in the first place: Almost lost amid the Billy worship is the fact that moneyball has never netted Beane a World Series win.) Indeed, the A’s may have been thwarted in their move to San Jose, but spiritually, at least, they’re Silicon Valley’s chosen team, their manager an avatar for its number-crunching, resource-maximizing, status quo–disrupting ethos. After all, Beane’s recent trades are essentially the baseball analog of that famed Facebook maxim: Move fast and break things. As Beane’s friend Zach Nelson, CEO of the San Mateo software company NetSuite, says admiringly, “At the end of the day, you have to pull the trigger. He has the courage to make the decision.”

Nelson is far from alone in his all-out devotion to the Church of Billy. CEOs brag about their moneyball hiring strategies, programmers use moneyball principles to allocate scarce software resources, and nonprofit directors follow moneyball maneuvers in trying to raise funds. (The appreciation is mutual—Beane credits the milieu of Bay Area entrepreneurship with inspiring his own worldview. “You’ve got companies like Oracle and Google across the bay,” he says. “You’ve got Stanford over there, and Cal over here. You bump into innovators. It’s very stimulating. We’ve always been intellectually curious.”)

Beane himself has profited nicely from these proximities. His bio on the website of Greater Talent Network, the agency that represents him for speaking engagements, reads more like a Fortune 500 exec’s than that of a former outfielder with a .219 liftetime batting average: “Billy Bean’s ‘Moneyball’ philosophy has been adopted by organizations…as a way to more effectively, efficiently, and profitably manage their assets, talent, and resources. He has helped to shape the way modern businesses view and leverage big data and employ analytics for long-term success.” Beane serves on several corporate boards, including those of NetSuite and sports equipment manufacturers Riddell and Easton-Bell Sports. Through Greater Talent, he has addressed conferences sponsored by software companies such as Palo Alto’s Adaptive Insights and Redwood City’s Informatica. In fact, September wasn’t just about pennant races for Beane: He also addressesd the Healthcare Analytics Summit in Utah and LinkedIn Sales Connect in San Francisco.

Nelson invited Beane to join the NetSuite board because in the battles between the A’s and the big-market New York Yankees, he saw the travails of the small businessews to which NetSuite sells software—and a metaphor for his company’s own battles against giants like Oracle and SAP. Nelson, whose work involves persuading executives to move their systems to the cloud with his products, commiserates with Beane about his challenges. “There are lots of managers in baseball who still manage by their gut and don’t really understand the statistical significance of their decisions,” Nelson says. “In IT land, it’s the same thing. People go with what they know.”

Earlier this year, when A’s pickup Kyle Blanks was terrorizing pitchers with a .333 average, Nelson asked Beane how he had nabbed him so cheaply. It was simple, Beane told him: Blanks only hits lefties. His previous team used him every day, and he struggled, but the A’s platooned him, and he thrived. “Other managers would say, if he’s hitting lefties, let’s try him against righties, even though the numbers are staring them in the face,” Nelson says. “Even the simplest stuff is hard for the old line to digest.”

Prakash Nanduri, CEO and cofounder of Redwood City big-data startup Paxata, says that he can’t afford to give all the perks that bigger companies offer—but he can mentor employees and provide opportunities for advancement. “If you work with moneyball recruiting and moneyball professional development, you can create those next superstars,” he says.

Rob Gitin, executive director of At the Crossroads, a San Francisco nonprofit that works with homeless youth, says that Beane’s thinking has influenced his organization’s fundraising strategy. “It’s not like I wear a ‘What Would Billy Beane Do?’ bracelet,” says Gitin, “but I do think about these things.”

Sean Graves does, in fact, own an “In Billy We Trust” poster and T-shirt. Graves, director of marketing at Rethink Studios, a Chicago special effects firm, is an Oakland native who moved to Chicago with no connections, wrangled an internship, and persuaded his employers to make him the social media coordinator. “I don’t know if Billy Beane has been something I’ve been cognizant of when I’m taking risks like that,” Graves says, “but watching the A’s always trying something new since I’ve been one year old, it makes an impression.”

For his part, Beane claims to avoid the spotlight. According to A’s PR director Bob Rose, Beane turns down 9 out of every 10 interview requests. In person, the cocky commando of Moneyball and the personality behind the cult comes across determined to be humble and self-effacing. “I’ve never felt like everyone needed to hear what I want to say,” Beane says. “That’s why I’m not on Twitter. Where I’m going to get my coffee that day is really not that important. My most important job is as a husband and a father to three kids. I’m their soccer coach. Anything that erodes from me being a regular guy makes me feel uncomfortable.”

“My grandfather flew airplanes in World War II,” he continues. “My father was a military officer. I like to think I’ve got a handle on what things are important. I’m lucky because I get to trade baseball cards and get paid for it.”